We Perceive (Partly) What We Expect

Getting human cognition less wrong with predictive processing and neurodiversity.

Here's something most people don't often think about: the extent to which you can understand yourself or anyone else is limited by the extent of the wrong assumptions you have about how brains work.

Understanding yourself and understanding anyone else are ...pretty important topics, both personally and politically. I'd say current events underscore that fact: WTAF are these people thinking??? Yet we all have some seriously wrong assumptions about cognition, they're often pretty deeply ingrained, and it can be hard to find reliable sources for general updates on our scientific understanding of how we humans think.

Even so, we do have the ability to update those working assumptions. In this post, I'll highlight a couple of the handiest conceptual tools to help get the brain less wrong every day.

If you want to understand where modern cognitive neurosciences are going, you have to look in the process-relational direction. This fundamental way of understanding things in general—basic metaphysics, if you will—observes that what primarily constitutes the world are processes and their inter- and intra-relations, including in nested systems. This view is distinguishable from the other main direction, "map-metaphysics" on this blog and "substance metaphysics" elsewhere. That way asserts that what primarily constitutes the world are discrete, isolatable individual entities. These separate entities are sharply distinguished from what they are not and are defined by determinate and largely static essences. If you've read other posts here, you know the drill. Process-relational metaphysics gets the complex territory of reality empirically less wrong across the board. Brains are no exception.

When you do look in that process-relational direction in neuroscience, there's a lot of immensely cool stuff happening. I wrote in a previous post about the revival of brain laterality studies (i.e., left vs. right hemisphere characteristics) and how the hemispheres' respective modes of operation align astoundingly well with those two main ways in which humans understand the things that constitute our world: isolating, essentialist, reductionist, and control-oriented on the left, and integrating, dynamic, emergent, and context-oriented on the right. Unfortunately, dominant Euro-Western culture and philosophy have decreed left-brained map-metaphysics to be more "rational." That reality-denial often has some pretty bad consequences, like rigid hierarchy, othering, siloing, and inability to solve or even ask the right questions about gnarly interconnected problems.

This post focuses on another broadly two-directional gradient to how we think, called predictive processing, in the context of the surging neurodiversity movement in science and society.

Insight on Sight

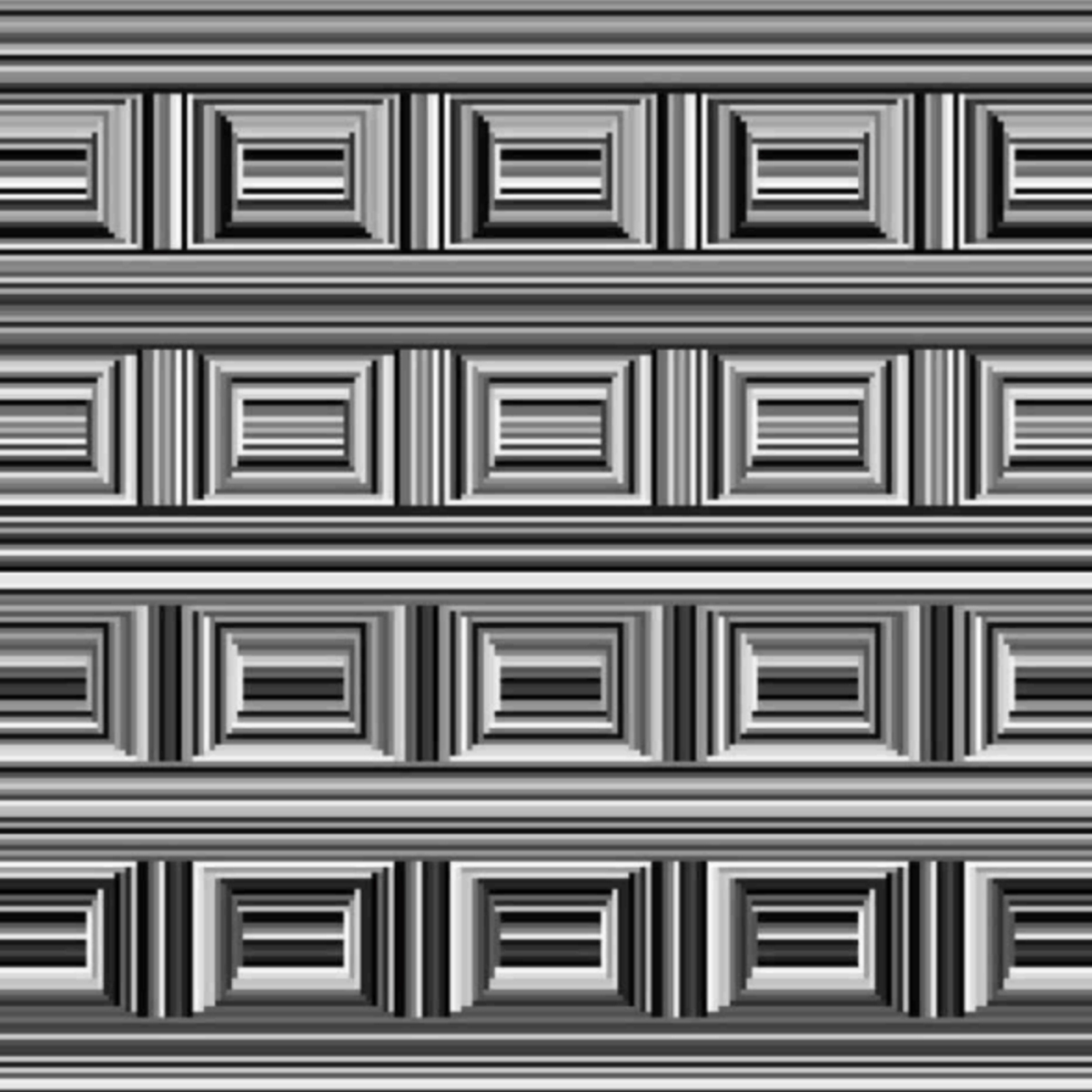

I was prompted to write this post by a very cool article published recently in Science magazine. It's titled "Culture literally changes how we see the world," with the subhead "where city dwellers see rectangles, people who live in round huts see circles." It discusses research on perception of visual illusions like this one, called the Coffer illusion:

What do you see? If you're like me and almost all Euro-Westerners, you see rectangles. But it's equally correct to see circles! I, and many others, would not have even seen any circles at first unless prompted to expect them; even so, it's still a bit of a struggle, and the rectangles dominate. If you need an assist, there are sixteen circles, formed by the rectangles' corners; try looking for vertical lines to pop out against a background of horizontal ones. "The researchers suspect this is because [people from the U.S. and U.K.] are surrounded by rectangular architecture, an idea known as the carpentered world hypothesis. In contrast, the traditional villages of Himba people [from rural Namibia] are composed of round huts surrounding a circular livestock corral. People from these villages almost always see circles first, and about half don’t see rectangles even when prompted."

These inverse defaults come from differences in visual mechanisms themselves more than higher-level attentional control or interpretation. In other words, there are cultural and other differences in perception itself, literally what we see, not just in how we interpret what our senses tell us—because perceiving and processing are not separable things. Perception is a contextually situated system of ongoing active engagement with the world, not a passive intake. One cognitive scientist called this striking cultural difference in perception itself (adorably) "a real humdinger."

The article also notes that "although many anthropologists and psychologists have long accepted that culture and environment play some role in vision, the significance has been slow to spread among vision scientists, who rarely include people from other societies in their research," illustrating how siloing, separation, and assumptions of view-from-nowhere universality hinder our understanding. Without taking cultural and environmental contexts into account when studying how the mind works, researchers "risk mislabeling things as universal human features when in fact they are side effects of the researchers’ own culture—a culture that is unusual by global and historical standards. ... [Study coauthor Michael] Muthukrishna adds that although it’s important to learn what humans have in common, the differences matter, too. 'It shows the importance of diversity,' he says. 'If you’re trying to get a full picture of the world, you want to have some people in the room who see circles where you only see rectangles.'"

The Predictive Brain

This Science article doesn't specifically mention predictive processing, nor does the preprint it discusses. They don't aim to tease out the mechanisms behind the encultured expectations-based differences in perception that the study proves. But my mind immediately leapt to The Experience Machine, by Andy Clark, and other fascinating research and writings on predictive processing. It's increasingly a matter of consensus among those in the know that our brains don't passively take in the world through our senses from outside like cameras or microphones, and then internally interpret those perceptions, no matter how much it feels to us like that's what's happening. Rather, our brains are always proactively anticipating and bringing a significant dose of our own multi-level predictions to the process of perceiving. That process is constantly and speedily negotiated, mostly beneath our consciousness, among:

- predictions from deep inside the brain, often beneath our awareness, including both higher-level and more stable generative models and the moment-to-moment predictions they shape;

- the incoming sensory information that checks those predictions' errors; and

- the brain's best estimate of each side's relative reliability and significance at any given moment, somewhat confusingly (IMHO) called "precision weighting." Strong emotions are among the factors associated with higher precision.

It's the results of that negotiating process, never the "raw" or "unfiltered" incoming sensory signals, that we experience. Those results then iteratively refine future predictions. This fact has major implications. Clark notes that this contextual and prediction-driven process "does not mean we can never get things wrong. But it does mean there is no single way of getting things right."

While many questions remain about how exactly this happens, the new model explains a lot that the traditional, more passive model can't. For example, it's well settled that neuronal connections are far more numerous in the "backward" or "downward" direction from the brain out to sensory intakes like the primary visual cortex than in the "forward" or "upward" direction deeper into the brain. This makes a lot more sense if perception is driven by those downward predictions. Additionally, leveraging predictions greatly enhances efficiency in the brain in a similar way to how predictive coding data compression does in telecommunications, helping explain how human brains do so much on about 20 Watts of energy. Predictive processing also explains various visual and auditory illusions, like that blue and black (or was it gold and white?) dress that took the internet by storm in 2015; placebo effects; otherwise unexplained functional disorders; the reality-steering power of positive or negative self-talk ("I believe that we will win!"); and why it's so hard for evidence to change our thinking when we have strong or emotionally invested expectations or "priors."

Some predictive processing models go so far as to argue that prediction error minimization explains absolutely everything the brain does in a very computational and frankly map-metaphysics-esque way. Clark comes close to this at times, including with the machine metaphor of his book title. I obviously think that likely understates the emergent complexity of biological cognition. Regardless, the core idea that we never experience the world "out there" "objectively" or "as it is," and instead always bring our culturally-shaped predictions to our experience of the world, appears to be a solid baseline for getting ourselves and one another less wrong. By recognizing each person's experience of the world as an overlapping but unique relational process, we can teach and learn to expect better. As Clark concludes:

[H]uman minds are not elusive, ghostly inner things. They are seething, swirling oceans of prediction, continuously orchestrated by brain, body, and world. We should be careful what kinds of material, digital, and social worlds we build, because in building those worlds we are building our own minds too.

I should acknowledge that the issues of consciousness and free will are elephants in the room for any discussion of cognition, and I daresay process-relationality helps here as well. I don't claim to have fully solved these issues, nor to be able to sort out who if anyone else has. However, it's a lot easier to imagine them being solved if they're properly thought of as emergent, context-situated, boundedly-indeterminate processes rather than as reified, ontologically unique sorts of substances that you either have or not.

Neurodiversity

All that might be more than enough mind-blowing cognitive science for one post. But process-relational reality also points us towards the correctness of the neurodiversity paradigm, for essentially the same reasons as it points us toward cultural perception diversity in the visual example above. Both models have highly overlapping and mutually reinforcing implications for understanding ourselves and others, including in the political sphere.

The neurodiversity paradigm is best introduced in contrast to the Euro-Western conventional medical model, which is thoroughly grounded in map-metaphysics. Cognition is an isolatable thing set inside the individual brain, best studied by reductionist methodologies. There's essentially one normatively right way to do it, defined primarily by elite white men in terms of (at least aspirationally) rigid, unchanging and universal diagnostic criteria. Deviations are pathologies of the deviating individual to be treated back toward normality by specialists—if not simply condemned or exploited. To be sure, there has been progress made under this model on a number of fronts, but that doesn't mean the model can't be vastly improved upon.

The neurodiversity model, developed in large part by neurodivergent people themselves, takes a big leap forward in a process-relational direction. It recognizes cognition as an integrated process with multiple valid ways of going about it depending on complex and contextual factors. These ways are not objectively rankable. With no single universal standard, diversity is the norm and is valuable to our ability to know things. Neurotypes, including those known as autistic, ADHD, and many others (they can of course overlap), are shaped by processes involving genetics, development, environment, and culture.* What is problematic for well-being must be defined in relation to people's situations and addressed with an awareness of systems; often this will look like teaching more neurotypical or neuronormative people how to change their thinking, which turns out to have its own trade-offs. All perspectives matter, even if some views can be shown to be more or less wrong than others by well-grounded multi-perspective evidence.

It’s tremendously practically useful to understand our perception and cognition as uniquely situated, heavily prediction-based relational processes, shaped by neurotype as well as by culture, personal history, and circumstance. This understanding can benefit our decision-making in daily life as well as in strategizing for transformative political change. On the personal scale, it can nudge us to give greater consideration to the possibility that our predictions and cultural conventions might be distorting our never-"objective" perceptions of reality, or that different and even contradictory others might be equally valid and necessary. In other words, it's a concrete scientific reason for the careful intellectual humility that's so crucial to getting things less wrong. On a community and societal scale, it can help us prioritize changes to the media and information environments that shape people's expectations and minds; appreciate and structurally accommodate cultural and neurotype diversity as not just inevitabilities but problem-solving assets; improve our ability to persuade across wide perspective differences; and expand our horizons for imagining how different our societies really could be. It may not be easy for many Euro-Western folks to accept the impossibility of a perspective-independent “one-world world” that's simply out there to be objectively perceived as it is—but there are a lot of advantages to that view, first and foremost that it's true.

*There's an especially fascinating crossover between the autism spectrum part of neurodiversity and the predictive processing model, in which autistic people may have core differences in precision weighting that explain a whole lot... but that's a topic for another post, perhaps.