Transforming Economics in a Time of Global Crises

A game-changing article clarifies ways to go beyond extractive capitalism to a reality-based economy.

This past weekend of increasingly open fascism was unfortunately a great one for illustrating the need for diverse, justice-oriented information sources like I talked about in Part II of my Top Tips series; mainstream media shit the bed in many respects. I, however, had a lovely weekend. In addition to three fabulous birthday dinners (fancy schmancy with husband, Dew Drop Inn with husband, casual with friends), I also experienced the sublimely nerdy joy of gaining a new favorite written work. In one sense, it's only indirectly related to current events. In a truer sense, it gets right to the heart of what's going on and what to do about it.

This entry to my personal canon is an article published late last month in the prominent journal Nature Sustainability by fifteen highly esteemed authors, primarily economists. It's titled "Ten Principles for Transforming Economics in a Time of Global Crises." I know that doesn't sound like a fun read to most, but it's already cemented in my evaluation as one of the most exciting, game-changing intellectual advances that people should know about. They probably won't because, well, it's an analysis article about transforming economics published in a peer-reviewed sustainability research journal. But I'll try to do my little part here to make its fascinating insights more accessible and mainstreamed, with an assist from the basic comparative understandings of reality—i.e., metaphysics—that are the obsession of this blog. (To avoid repetitiveness, I put a 2-minute intro to that empirically-based "map-versus-territory" concept as a footnote* to this post. To those new to this blog, I strongly recommend that you skip ahead to that now; for more, see here and here. I promise it's a tremendously useful concept to know.)

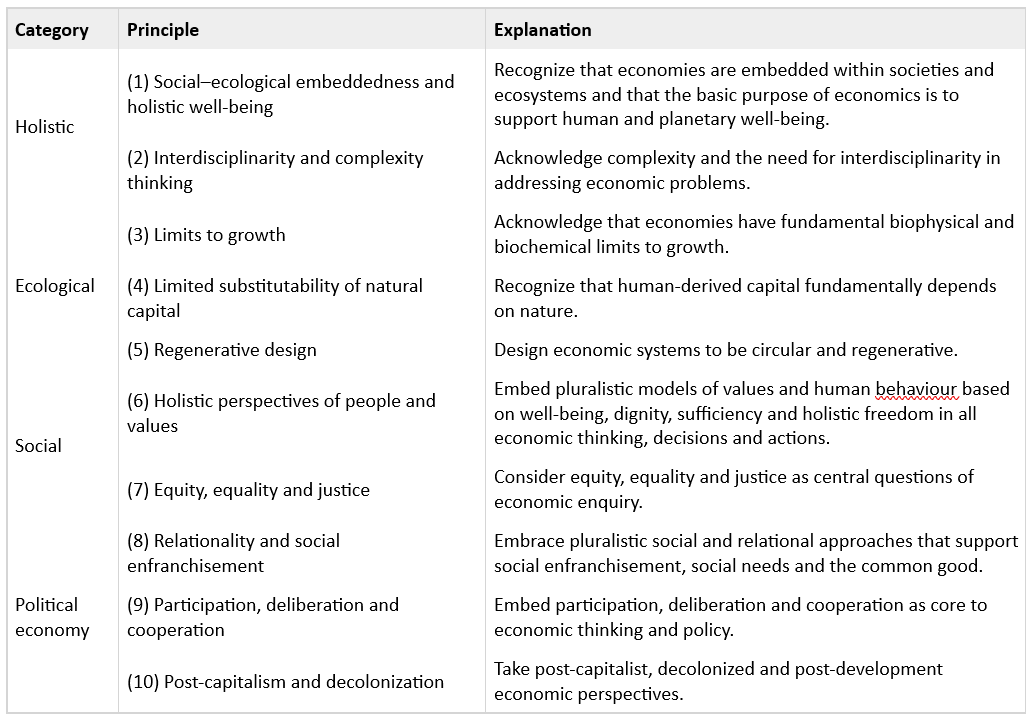

What makes this article so impactful is the way it integrates disparate perspectives and knowledge sources, consolidating insights from their overlaps while respecting their differences and complementarities. Just like I recommend. Drawing from hundreds of economics articles, books, and institutional and conference reports, the authors compile a set of ten holistic, ecological, social and political principles. By bridging across perspectives, these ten principles can catalyze more cohesive discourse coalitions to better challenge conventional thinking and vested interests; facilitate more organized action; and gain more traction to transform our stories, paradigms, and economic and policy regimes. Such transformation, in turn, is urgently necessary to stave off the worst of our intertwined and compounding crises and to salvage the chances we still have to build a better world for everyone. Most of us want that, right?

Without getting too much into methodology, it's worth emphasizing that to undertake their qualitative content analysis and draw out cross-cutting principles, the authors reviewed thirty-eight (38!) approaches that are alternatives to currently dominant, basically neoclassical capitalist economics. None are communism or socialism. The binary idea that there are only those two options for the study and governance of "the production, consumption, valuation, allocation and exchange of goods and services," capitalism versus communism/socialism, is some of the stickiest and most sadly effective capitalist propaganda out there.*** It's also plainly wrong. A few of the economic approaches analyzed in the article are components of Indigenous worldviews, such as ubuntu (sub-Saharan), kaitiakitanga (Māori), and buen vivir and sumak kawsay (Andean). Others are more Euro-Western, like well-being economy, doughnut economics, ecological economics,** cosmolocalism, and enlivenment. So many alternatives! In your face, capitalist realism.

In addition to the idea that alternative economic approaches beyond capitalism and communism are not only possible but already being proven out in practice, the main idea I'd like to leave folks with is... drumroll please... that transforming economic systems and structures to save our asses entails embracing the process-relational terrain of reality and rejecting simplistic, separating and essentializing map-metaphysics misunderstandings of things. Yep! We can see the latter in many of mainstream capitalism's load-bearing assumptions and abstractions, including that nature is separate from, and a resource for, humans; that individuals are largely rational self-interest maximizers who behave according to generally fixed rules; that "externalities" are merely peripheral "market failures" and not fundamental challenges to the models; and that central economic goals are the pursuits of market optimization, endless growth, and affluence as measured by simplifying (and highly distorting) monetary yardsticks like gross domestic product (GDP).

On the other hand, while not all 38 alternative approaches emphasize all ten identified principles or fully transcend map-metaphysics, all ten principles to address our global crises align with process-relational reality. One could say there's just one lowest-common-denominator principle that everything else can largely be extrapolated from: that human inquiry has conclusively established that the things that comprise the world are best understood as processes that mutually co-constitute themselves and one another through their dynamic relations, not as the sharply separate, self-contained entities with determinate essences of Euro-Western and capitalist convention. There's value in breaking this out into a manageable number of distinguishable principles, and there's also value in recognizing their unified direction.

Here's a summary table of the ten proposed principles, clustered into four themes.

It's worth fleshing these out a bit, partly to see how we can apply each one in our day-to-day business even if we don't do formal economic analysis ourselves.

While the word holistic has been tainted by its wrongful association with wellness woo-woo, all it means is being concerned with whole systems rather than only dissecting into separate parts. This is hard to do with a baseline misunderstanding of reality as constituted of fundamentally separate parts, as map-metaphysics proposes: "carving nature at its joints," in Plato's illuminating butchery metaphor. It's pretty easy once you understand reality to comprise relational processes that co-constitute one another in an "inescapable network of mutuality." The first holistic principle of social-ecological embeddedness recognizes that "all economic relations are social–ecological relations. Well-being is conceived as embedded in these relationships, with human and planetary well-being interdependent. An explicit goal is to align economic welfare with planetary well-being." My day-job colleagues in equitable clean energy promote this goal (among others) every day.

The second holistic principle elevates the intellectual humility practices of integrating interdisciplinary and pluralistic sources and of acknowledging complexity, emergence, and nonlinear dynamics. "Conventional neoclassical models reduce real-world complexity to an abstract set of production and consumption measures, which narrows possibilities and can drive problematic policy outcomes, for example, in addressing highly complex problems such as climate change." Capitalist economics' simplified maps are poor approximations of the process-relational territory of reality, which is forever beyond its component humans' (or artificial intelligences') capacity to fully know and control—but not beyond alternative economic approaches' capacity to help us navigate.

Building on the holistic principles of relational embeddedness and complexity, many alternative approaches are grounded in ecological understanding and overcoming the false Cartesian divide of humans versus nature. Principle three recognizes the irrefutable, yet often ignored, fact that there are fundamental limits to the rates and kinds of growth that are possible. These limits mainly relate to material planetary boundaries (again, only Earth matters, Mars colonization is bullshit) and to what the article authors call "societal metabolism," our capacities to handle flows and changes. Principle four, then, recognizes that everything we have ultimately derives from the nature of which we are a part, and that the gifts Earth provides are not fully commensurable or substitutable with one another or with money. In other words, we can't eat money or buy our way out of ocean current breakdown. And principle five is about designing systems to be regenerative, or maintaining positive reinforcing cycles of wellbeing. I've raved about regeneration before as core to a process-relational world's self-maintenance.

The next couple of principles focus on predominantly social themes. The sixth centers on pluralistic, inclusive, relational and socially regenerative considerations for why humans do things. It rejects the orthodox "rationalist" model of "homo economicus" and its downplaying of factors like liberty and dignity. These more diverse whole-person valuations and motivations, needs and capabilities, can be embedded in economic institutions, models, and decisions. The seventh principle holds equity, equality and justice to be central questions of economic enquiry. It challenges orthodox economics' map-metaphysics-based fact-value dichotomy and its narrow, top-down model that dogmatically emphasizes "efficiency" and excuses inequality among who benefits and who suffers. Keeping distributional, social, and environmental justice at the core of economics is demonstrably necessary to avoid wrong assumptions and achieve resilience and regeneration benefiting everyone. An economic approach that boxes these out from consideration isn't "objective"; it's trash.

To round it out, the authors present three principles pertaining to reshaping the political economy for inclusive participation and belonging. Principle eight is relationality and perspective pluralism, so that's obviously on point. There are many alternative economic approaches that integrate relational values such as care, reciprocity, community land stewardship, and love into their models, processes, and goals for the common good. This requires new quantitative and qualitative metrics for things that current mainstream economics defaults to assigning zero value, along with other new evaluation and accountability structures. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), a United Nations organization, has been a leader for years in assessing ways to incorporate pluralistic and relational values and methodologies into real-world analyses and decision-making.

The ninth listed principle highlights how much processes make things what and how they are. It therefore acknowledges the need to embed active cooperation of broadly-defined stakeholders at the heart of economic thinking and policy. These processes can certainly utilize modeling and analytical, data-heavy methods, but even technical parameter choices are ultimately values-based. "[C]onflicts between values cannot be fully resolved through optimization but must be democratically deliberated through methodologies such as participatory action research, participatory systems modelling and deliberative valuation. ... While cooperative perspectives have received some scepticism in conventional economics, institutional and feminist economists have pointed them out as common practice, benefiting sustainability, productivity and equality." I think the phrase "nothing about us without us" is relevant here.

The tenth and final principle underscores the depth and ambition of transformation to which we can and should aspire. It puts post-capitalist, post-development, decolonial, and other perspectives conventionally marginalized by mainstream Euro-Western thought front and center, not just at the table or in the mix of considerations. To transform economics enough to bring it in alignment with well-being within planetary limitations and other aspects of process-relational reality, we will need to disrupt deeply embedded concepts and structures and to reclaim power through new or transformed institutions. This principle encompasses various contextual approaches and tools for achieving that. I'll indulge in a slightly longer excerpt to illustrate some of the range:

At the microeconomic scale, sharing economy and post-capitalist approaches envisage economic practices based on new technologies and a reduced need for labour, including new currencies that embed social and ecological values, communal ownership, new forms of cooperatives and online networking spaces to promote non-profit forms of work and address labour mobility, empower disadvantaged individuals and support capabilities. Cosmolocalism envisages collaborations between globally connected citizens and grassroots movements to transform consumption–production regimes through digital innovation, strengthening both local, social–ecologically embedded economies and global citizenship and multilateralism. At the macroscale, degrowth, post-growth, ecological, steady-state and post-Keynesian economics provide new analytical tools in areas such as monetary and physical input–output and system dynamics modelling, whereas post-development theory affirms cultural diversity, aligns new economics with indigenous philosophies, promotes democracy and provides social spaces for conflict resolution and social protocols associated with reciprocity and respect for nature.

Mainstreaming of these ten principles, and of the overall process-relational reality that they all point towards, would have tremendous practical benefits. For one, shared language and stories would enhance the ability of different approaches that have been siloed away from one another to engage in more productive discourse. This extends beyond the approaches analyzed in the article. Economics matters to more than economists, and it deserves the input not only of the dozens of alternative approaches reviewed, but also of "external" domains like physics, biology, and humanities. The tie-in of empirically-supported process-relational metaphysics with these principles can serve as a strong shared foundation for these interdisciplinary contributions. Metaphysics, after all, is the only topic whose domain covers literally everything.

Building on that discursive benefit, increasingly cohesive efforts leveraging these shared tools can build momentum such that efforts supporting individual elements, like circularity or relational valuation, "become a springboard towards broader transformation, rather than a way to evolve neoclassical economics without fundamentally challenging vested interests." Niche initiatives can connect into broader networks for amplification. What's now heterodox can, with intentional organizing, become a new paradigm. That's huge. It's a practical vision of non-reformist reforms: real movement toward true societal transformation beyond unsustainable and exploitative capitalism that doesn't require waiting around for a violent revolution and hoping for the best.

Embeddedness, complexity, material limits, nature dependency, regenerativity, whole-person perspectives, social justice, relationality, participatory and cooperative process, decoloniality. These ten spokes revolve around a central, trending shift in our understanding of how things, in the broadest possible sense, hang together, in the broadest possible sense—that is, a shift in metaphysics at the most basic, directional level. The rubber meets the road, so to speak, where these principles increasingly shape thinking, discourse, decisions, actions, institutions, structures, and systems. Current events make the high stakes of this ongoing war over reality plainly evident. As the Nature Sustainability article authors conclude: "unless the ideas summarized in the ten principles are rapidly embedded in global and national institutions, humanity is unlikely to overcome the extreme crises it is facing." Alrighty then, time to get rolling.

*Basic comparative metaphysics 101 in under 500 words:

You and everyone else are constantly, if implicitly, applying metaphysical frameworks. There are many diverse ways of conceptualizing what kinds of things constitute existence, what it means to be real, and so on. However, from a maximally zoomed-out perspective, they largely cluster into a gradient of two primary directions. One is substance or substantialist metaphysics, the direction that has been dominant in Euro-Western cultures for centuries, built on a primacy of separateness and fixity. The other is process-relational metaphysics, the direction that is more common among non-Euro-Western cultures worldwide and increasingly ascendant in empirical sciences as well, including physics, biology, cognitive science, social sciences, and beyond. These two directions may correspond to the primary modes of our left and right brain hemispheres, respectively; at any rate, everyone is capable of both directions, and much comes down to which we are taught (or what we choose) to trust.

Substance thinking is called "map-metaphysics" on this blog because it mistakes pinned-down human mental models and simplifying, isolating abstractions for the true terrain of existence. It sees reality as made of fundamentally separate and self-contained things, like particles. Things in this view are generally defined in sharp either/or distinction from what they are not, mainly with reference to static, determinate essential attributes or membership in idealized and likewise separate natural kinds. Endurance of things and kinds is taken for granted, and change must be explained. This view gives the illusion of contradiction-free clarity and control. It undergirds other perceptions of how reality works and how we understand it, including binary logic, view-from-nowhere "objectivity," reductionism, quantification primacy, siloing, individualism, othering, rigid hierarchies, and zero-sum competition. In the Cartesian dualist version of this metaphysics that still pervades Euro-Western culture, mind is separate from mechanistic matter, with comparable divides between subject versus object, culture versus nature, and hard (abstracting, self-interested, competitive, quantitative, masculinized) rationality versus fluid (embodied, caring, mutualistic, qualitative, feminized) feeling.

By contrast, things as relational processes are more wave-like, even if they're particles or solid objects: everything flows. They are intertwined, mutually shaping, and ultimately defined by relations and the persistence of coherence. Multi-level interactions among systems and processes of change and stabilization are what make things what they are (e.g., you are you as a result of cell metabolism, family, culture, formative events, evolution, environment, etc. etc.). Mind and matter, culture and nature, and so on are mutually co-constituting, distinguishable but inseparable and overlapping. Reality emerges from and as a dynamically interdependent web or network of events. Change is taken as the baseline, and endurance gets explained in terms of process stabilization over various scales of time and space. Real things are never truly isolated or frozen as in substantialist models. Contradictions sometimes happen. This general view supports other perceptions of how reality works like contextually situated knowledge, pluralism, complexity, emergence, unknowability, integration, reciprocity, and care.

**While social-ecological economics (SEE) does not get separate analysis in this research article, it's an evolving approach that intentionally integrates the best lessons of these approaches and others as well as all ten identified process-relational principles. I'd say the same of integrated knowledge theory, which is closely aligned with SEE.

***This may deserve its own post, but a main reason communism sucks is because, like capitalism, in practice it's a substantialist or map-metaphysics oversimplification and reification of primarily separating and essentializing concepts that treats some people and places as disposable. Most dedicated communists and Marxist theory-bros aren't as radical or revolutionary as they like to think.