Top Tips - Part II

What we should let through our information screens and how we should put it together.

In Part I of Top Tips for Navigating a Garbage-Fire Info Environment, we got a 30,000-foot view of the two directions of basic comparative metaphysics and a tiny preview of the vast, convergent empirical evidence for process-relational reality. We also saw how that can help provide a solid basis for screening out unreliable news and information sources that mistake their simplifying maps for the territory and conflict with reality as it should be understood.

Now, let's look at what we should let through our information screens, and at how we can usefully put it together for trustable knowledge of our shared yet pluralistic reality. Such knowledge is good in its own right, of course, and it's also essential for self-governance and resisting political domination, so these information-navigating tips double as resistance tactics against fascist consolidation of power.

What's In

Process-relational green flags for sources or information generally mirror the red and yellow flags in Part I. They include:

- Transparency and relevance of perspective. Ask where they’re coming from and be wary of conflicts of interest, as well as of experts in one domain claiming authority in another. Also ask who they're accountable to, including funders.

- Transparently justified study topics and designs, algorithms, and/or other framing/agenda-setting choices, as applicable, that admit and control for distorting biases as much as feasible.

- Contextualized coverage and systems analysis (e.g., “not the odds but the stakes,” per journalism professor Jay Rosen). Because there's so much possible context to draw from, it can take practice to distinguish informed contextualization and systems analysis from defensive whataboutism or conspiratorial and still-decontextualized dot-connecting, which are red flags. Understanding motivations is helpful.

- Engagement with and convergence from multiple different perspectives (disciplinary, cultural, technological, etc.). Just coming from a different perspective than one’s own is also valuable.

- Peer review and collaboration, openness to good-faith critique, and genuine dialogue—not merely debate.

- A track record of accuracy. For example, people who came close to rightly anticipating the lawnessness, segregationism, eugenics, and horrific destructiveness of this Trump regime and Project 2025 should be trusted and platformed more than people who didn't.

- Evident incentives and accountability processes to find/admit/correct errors that do occur, and to admit limits of knowledge.

- Recency, with some caveats. Unless y0u have some reason to think a field of inquiry is moving in the wrong direction (e.g. because it's overcommitted to map-metaphysics assumptions or otherwise subject to distorting biases), a reasonable default is to check the most up-to-date information. Academic and professional fields tend to have at least some self-correcting and self-improving processes. That said, progress isn't linear and earlier people weren't less intelligent than today. Sometimes the old stuff is worth engaging directly.

- Moral clarity and alignment of methodologies/values/conclusions with process-relational reality's interdependence and regeneration. Absent any other indicators of distortion, "bias," impact orientation, and even passionate advocacy in favor of the conditions necessary for coexistence on Earth don't dent credibility whatsoever. They strengthen it, as I'll discuss further in the last section of this post.

I'll illustrate how I personally apply these red, yellow, and green flags. Most people's processes will be much less intensive, and that's totally fine. Not everyone's writing an interdisciplinary blog literally titled How To Get Things Less Wrong.*

Sources that integrate many expert perspectives and subject them to extensive review processes in order to provide a relatively authoritative overview, such as the Stanford or Internet Encyclopedias of Philosophy, other online encyclopedias, Annual Reviews and other reputable review journals, Oxford Bibliographies and Handbooks, or CRS reports, are generally my first-line sources if I'm starting out on a topic. These usually address both consensus areas and major points of disagreement or controversy. Wikipedia is also a perfectly acceptable starting source on the vast majority of topics, especially for pages rated B-class or better. You can check by clicking on the "Talk" link right below the article title.

Popular U.S.-based news publications that are mostly meeting the moment with accurate and contextualized coverage include Wired, Rolling Stone, ProPublica, and Teen Vogue (seriously). Reuters and Associated Press are generally (not always!) reliable and fast, albeit often in a bare-bones, low-context kind of way that doesn't necessarily promote integrated understanding. Books are hit or miss, but when they're good, they're grrreat! Newsletters and podcasts have even lower hit rates, but they can be green-flagged too. Not a whole lot of television news shows (including major networks) or online video platforms (TikTok, YouTube) avoid red flags, which is fine by me as a cord-cutter elder millennial with a preference for text over video, but unfortunate overall.

Staying up-to-date on current events isn't necessarily as high a goal for me as understanding broader patterns, but to the extent I do track events outside of work stuff in close to real time, I currently tend to rely most heavily on my own personally curated list of sources on Bluesky (never X!). There's quite enough perspective diversity among good faith sources generally oriented toward relational reality and regenerative coexistence for this approach to avoid being a bubble or silo; disagreements are common, robust, and interesting. Specifically, I follow a mix of public intellectuals, investigative and independent journalists, worldwide scientists and other academics, #Blacksky, Indigenous perspectives, disabled perspectives, queer and trans perspectives, urban and rural working class perspectives, international news media, Bulwark-type good-faith conservatives and libertarians, Marxists and other varieties of leftists, liberals, lawyers, seasoned activists, AI boosters and critics, religious perspectives, authors, nonprofits, and funny people. They often link solid primary sources. You could compile an entirely different, comparably diverse and reality-based list.

(I also use academic databases like Google Scholar, and occasionally subscription-only sources that are available onsite for Library of Congress researchers, to explore articles and their many citational cross-links. I love being humbled by how much expertise and scholarship there is. However, I do not recommend poking around these databases without advanced research methods and literature review training as they're overkill for most purposes, and it's incredibly easy to misinterpret research output.)

Again, this level and kind of engagement is far beyond what should be expected of most people, who have way less time and reason to do so much digging, and who are way less online than I am, to their credit. That's why I started with what to exclude. That tends to be more important for getting things less wrong, especially in today's noisy (mis)information environment. Uninformed is less troublesome and more fixable than misinformed. No news is better than hot garbage news. If microblogging like Bluesky disappeared, I'm not sure I'd be worse off, let alone the world at large. There's also no moral obligation to try to understand everything or to bear witness to all this shit. Touching grass and being in in-person community are vital sources of perspective, too.

How It Hangs Together

The screening tips above and in Part I mostly apply to evaluating the quality and reliability of individual sources or pieces of information, but no single perspective can carry the full reality of any remotely complex thing on its own. They have to be woven together to become verified knowledge and understanding. Like the broader reality-terrain of which it's a part, knowing is a process-relational web, not a collection of isolated items or abstractions on a map. Accordingly, the most crucial aspects of getting things less wrong are process-awareness and relational factors.

Perhaps the key process point is that getting things less wrong is a multi-step, multi-level, open and ongoing process. "Research with professional fact checkers demonstrated that the most efficient, effective way to both identify misinformation and find reliable information was to investigate the source. To do so, fact checkers engaged in lateral reading: they left unfamiliar sites, opened new browser tabs, and searched for information about the original site." Additionally, while knowledge-building is iterative, as with most processes, there are order of operations considerations. It's good to try to zoom out and get the gist, shape, and general concepts of a topic first as much as possible, because "understanding an area’s fundamental ideas creates the scaffolding for you to keep expanding your knowledge." Some of that general knowledge scaffolding or base layer is a matter of education access and largely outside a person's control. Nevertheless, I find that basic comparative metaphysics itself provides a good base of structural support for incorporating and organizing new knowledge, even from thoroughly un-knowledgeable starting points.

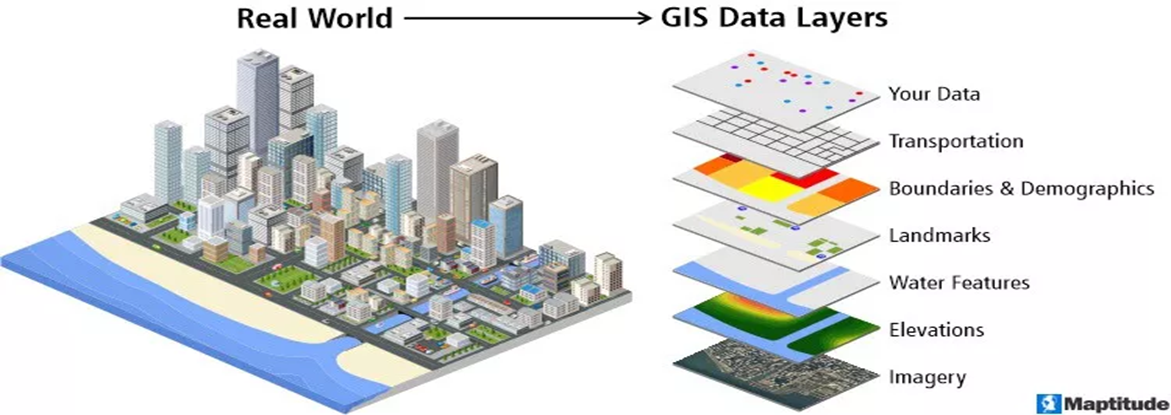

The goal of these processes is as robust a network of relations, among as high a number, quality, and diversity of relevant sources, as is feasible and worth the effort in the time you have. I like to visualize perspective-integrating processes as weaving a strong net, witnessing a scene from multiple angles, putting perspectives inside and outside of a silo in conversation, grounding a structure across a broader and more stable base, or melding dynamic data layers on an interactive geovisualization (see picture above). One might also envision diffraction, an image meant to convey the idea of reading perspectives including one's own "through" each other to glean amplification and interference patterns from similarities and differences, like ripples from multiple rocks thrown into a pond, rather than reading them reflectively "against" each other to see which one is best.

Whatever the metaphor, integrating across information points and sources is more than just collecting them, and more than mere consensus. The idea of consensus puts uniformity over diversity. It can sometimes amount to groupthink, top-down enforced unity, and suppression of differences. With a process-relational approach, both similarities and differences among viewpoints add depth and value. While subjective relativism would treat differing perspectives as separate and irreconcilable worlds, and objectivity would treat them as hindrances to finding the one universally best and most uninvolved perspective, process-relational views converge perspectives into an overall negotiated construction, a world of many worlds. A historian, a lawyer, a scientist, another scientist, and young and old community members might all help flesh out understanding of some event, including through their disagreements. Knowing is a community project that benefits from humility, genuine diversity, equity, and belonging.

What's Good: Morality Is Inseparable From Reality

The last points on each list of flags above might seem jarring because they refer to normative or axiological considerations. Euro-Western map-metaphysics convention suggests that it’s wrong or backwards for values, or what "should be," to influence epistemology or ontology about what "is." By and large, it says things objectively exist or not, and then we know them or not, and then we value them or not, in that order. In a process-relational reality, is and ought, like subject and object, or reason and feeling/affect, aren’t so starkly divided.

When things—in the broadest sense including people and the rest of nature—aren't isolated individuals but the stability patterns of relational processes, their existence, including their interests and well-being, is co-constitutive. Where no perspective is the single objective one, many perspectives matter. Their values aren’t generically commensurable and quantifiable. We must therefore consider and integrate value and the good from diverse perspectives in our shared reality, including the more-than-human.

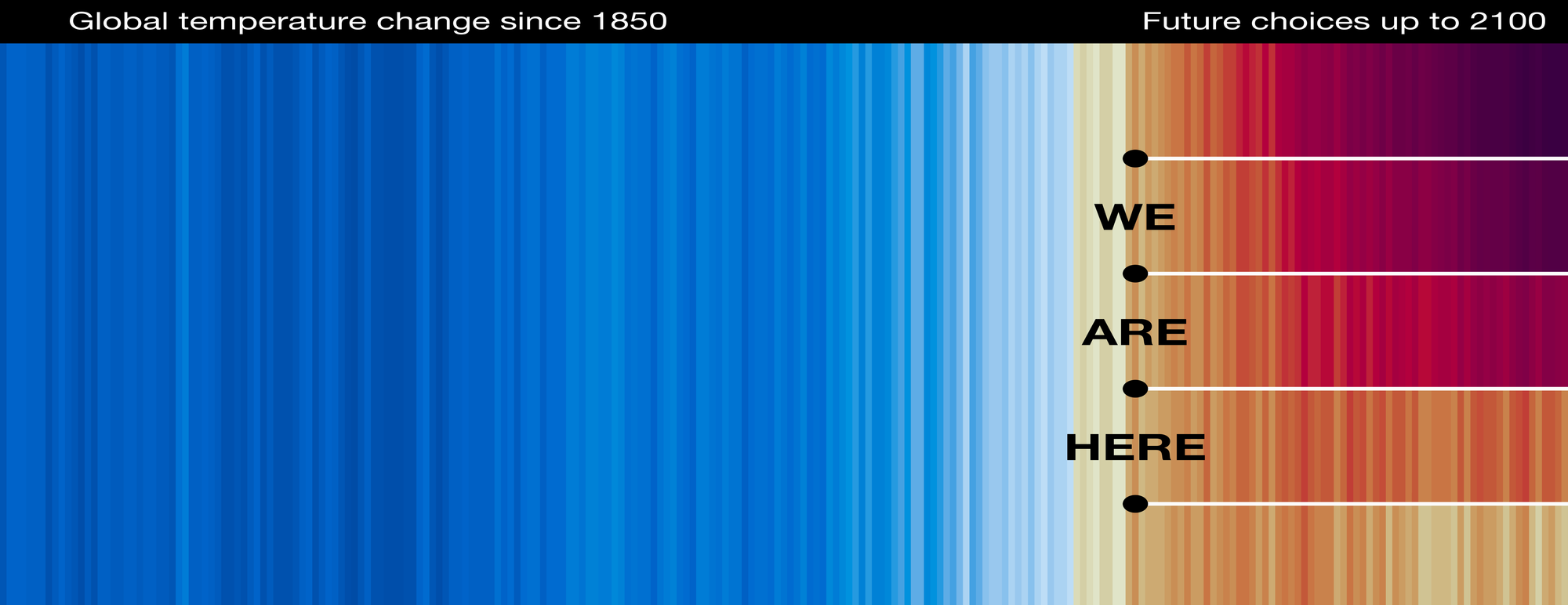

Once we do that, it’s evident that collaborative coexistence generates more value and good all-around than dominance for a few and subjugation for the rest. In fact, the latter, map-metaphysics, zero-sum competitive way of being ends up not only destroying value, but also inevitably degenerating the foundations of continued existence even for the dominant. The dynamically complex bio-geo-social conditions necessary for human existence build in and depend on a baseline of interdependent mutuality in order to persist. Convergent evidence confirms that good, in this relational and pluralistic lowest-common-denominator sense, is a major driver of how the world works without unraveling. It’s not an aspirational add-on after being and knowing. It's not opinion. Counting something as a gain when it comes at the cost of making things net-worse for other(ed) people or places is just plain bad math, cooking our only habitable planet** by cooking the books. Selfish resource hoarding and bunker mentalities are not "merely" unjust, they're structurally self-defeating in the long (but quickly approaching!) term; they’re anti-reality. People, knowledge disciplines, and cultures who understand this, understand the world better than those who don’t, and are thus more credible in general.

I’m borrowing the term regeneration to describe this baseline non-optional reality of dynamically interdependent eco-social wellbeing. In fields like product design and supply chain management, organization management, architecture and the built environment, policy, and beyond, the surging concept of “regenerative” has been hailed as “the new ‘sustainable.” It goes beyond sustainability or resilience concepts of reducing the damage caused by sustained systems. As summarized in a great 25-author framework article, things are regenerative if they maintain “positive reinforcing cycles of wellbeing within and beyond themselves, especially between humans and wider nature.” When regeneration is used in this manner, I see conceptual resonances toward restorative economics, with reciprocity and right relation as described by Robin Wall Kimmerer and others, and with Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s popular works on constructive climate reparations; the shared etymology of re- (turn/back/again) is not happenstance. Understanding things and people as separate, static, and so on pushes us in the opposite, degenerative direction; but a different, less wrong understanding is ours to choose.

Might leveraging basic comparative metaphysics and process-relational thinking to promote a more reality-based and regenerative information environment for ourselves and others help, at least a little, to get us to those positive cycles? After all, as Albert Einstein didn't quite say, we can't solve problems with the same thinking we used when we got into them. I think it's worth a try. To be honest, I don't see how we get there without collectively grounding transformation in our reality as it truly is, complex and messy and vibrantly beautiful.

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

-Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Well, there you have it: a highly condensed micro-course on taking in less-wrong information at a personal level by understanding reality at the most general level. Please sign up and comment below! I'd tremendously appreciate feedback, questions, additional tips, and dialogue.

Some links updated 2/1/26

*The title of this blog is mostly cheeky: a play on its obsession with "things in the broadest possible sense," the subject of metaphysics, in the proudly (?) punny tradition of The Matter With Things and Every Thing Must Go. But as this post series hopefully proves, basic comparative metaphysics is a useful tool for getting things in narrower, more specific senses less wrong too.

**Mars isn't happening, no matter how god-like you think AI will get. At least not for centuries or millennia, and that's wildly optimistic. Why would we think we (and who's "we"?) could manage the complexity of terraforming and stewarding a whole new hostile planet when we can't stop degenerating this literally perfect one? There's no Planet B and no existence but coexistence on Earth.