Real Process Biology

Subject matter experts have got my back on process-relational metaphysics.

You'd think living through these times would totally cure me of any imposter syndrome, but I'm still sometimes a little insecure about my credentials for this project. I have no doctorate. I didn't even minor in philosophy. I'm not a major author. I'm not sure credentials even exist for this kind of interdisciplinarity. Who am I to compare the metaphysics we all apply all the time? Why should anyone take me seriously on how to avoid mistaking the map for the more complex terrain when thinking about things?

Luckily, highly respected subject matter experts have got my back.

This post is mostly going to be excerpts from the first chapter in Everything Flows: Toward a Processual Philosophy of Biology (2018), by impeccably-credentialed editors Daniel J. Nicholson and John Dupré. This authoritative book is aimed at a non-philosopher audience and Oxford Academic has made it available free online; so, by metaphysics standards, it's fairly accessible. Nevertheless, I'm going to make it even more accessible by chopping 85% of it and distilling down the best bits, because that's my jam.

I should note that I personally find it easier to just loosely shorthand the framework as "things are relational processes" rather than distinguishing between things (taken to mean separate, static, essentialized substances or entities) and processes as this chapter does, though the end result is basically the same. I'd rather redefine "things" than give up on any thing really existing, and I suspect that would be most other folks' preference. I also find the authors' use of the term "hierarchy" a little muddling when there's not really any ranking or subordination, just mutually affecting levels of scale from sub-cellular to planetary. Those are superficial terminological quibbles, though. The chapter provides one of the clearest, most thorough introductions out there to contemporary Euro-Western process-relational thought and its advantages over our more standard substantialist or map-metaphysics assumptions. You have to read between the lines and extrapolate a little to arrive at obvious political implications, such as the wrongness of rigid gender binaries, individualistic health models, or extractive capitalism, but in some ways that's an advantage.

From Section 1, Introduction

The particular metaphysical thesis that motivates this book is that the world—at least insofar as living beings are concerned—is made up not of substantial particles or things, as [Euro-Western male] philosophers have overwhelmingly supposed, but of processes. It is dynamic through and through. This thesis, we believe, has profound consequences.

More specifically, we propose that the living world is a hierarchy of processes, stabilized and actively maintained at different timescales. We can think of this hierarchy in broadly mereological [parthood relations] terms: molecules, cells, organs, organisms, populations, and so on. Although the members of this hierarchy are usually thought of as things, we contend that they are more appropriately understood as processes. A question that arises for any process, as we shall discuss in more detail below, is what enables it to persist. The processes in this hierarchy not only compose one another but also provide conditions for the persistence of other members, both larger and smaller. So, if we take for example a liver, we see that it provides enabling conditions for the persistence of the organism of which it is a part, but also for the hepatocytes [liver cells] that compose it. Outside a very specialized laboratory, a hepatocyte can persist only in a liver. And reciprocally, in order to persist, a liver requires both an organism in which it resides, and hepatocytes of which it is composed. A key point is that these reciprocal dependencies are not merely structural, but are also grounded in activity. A hepatocyte sustains a liver, and a liver sustains an organism, by doing things. This ultimately underlies our insistence on seeing such seemingly substantial entities as cells, organs, and organisms as processes.

These processes—which have so often been taken for things, or substances— themselves engage in more familiar-sounding processes such as metabolism, development, and evolution; processes that, again, often provide the explanations for the persistence of more thing-like, or continuant processes. Do we not need things as the subjects of such non-controversially processual occurrences as metabolism, development, and evolution? Should we not be dualists, endorsing a world of both things and the processes they undergo? There are many responses to this line of thought, but the minimal condition for a position to count as a form of process ontology is that processes must be, in some sense, more fundamental than things. What this means, in very general terms, is that the existence of things is conditional on the existence of processes. Our own preferred view, which we shall elaborate upon later, is that things should be seen as abstractions from more or less stable processes. Peter Simons, in his chapter, suggests that things are ‘precipitates’ of processes.

From Section 2, Historical Background

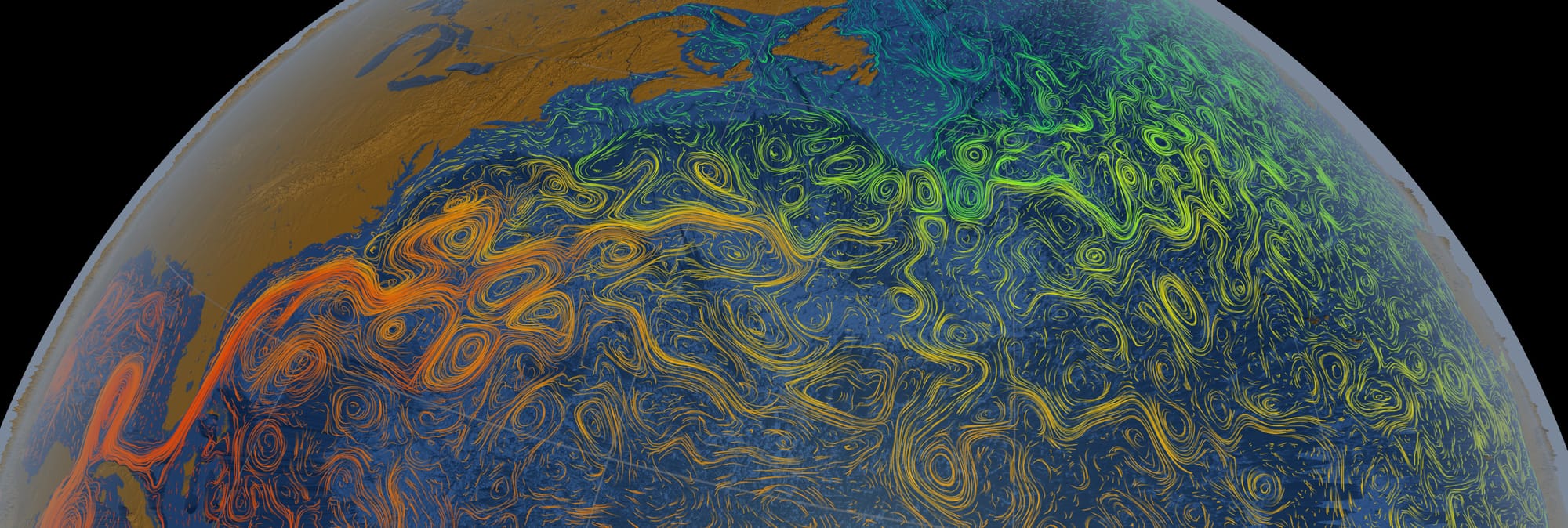

The opposition between things and processes as the ultimate constituents of reality is of course an ancient one, commonly traced all the way back to the Presocratics. Heraclitus is the patron saint of process philosophy, at least in the western tradition. The Greek dictum panta rhei (‘everything flows’) encapsulates the Heraclitean doctrine of universal flux. Heraclitus not only emphasized the pervasiveness of change, but also signalled the importance of change in explaining stability over time. The antithesis of this view is the atomism of Leucippus and Democritus. The indivisible and unchanging material atoms of the ancient tradition provided paradigms for the various notions of substance articulated in subsequent centuries.

Parmenides was another early advocate of substantialism. Although his static view of the world proved too extreme for most subsequent philosophers to accept, his conviction that permanence is more fundamental and more real than change became one of the cornerstones of western metaphysics. It was enthusiastically adopted by Plato in his changeless realm of eternal Forms—and also by Aristotle who, while transforming these essential Forms into worldly entities, nonetheless remained committed to their unchanging character. Aristotelian substances, which are the basic entities of his metaphysics, are distinguished as substances of particular kinds by their essence, and this essence sets unbreachable limits on the kinds of changes that an individual substance can undergo. It is difficult to overstate how influential this essentialist view has been. Many substantialists to this day follow Aristotle in asserting that, to be a thing, one must be a thing of a certain kind, and that the kind to which a thing belongs determines what changes it can undergo while still being what it is.

...

[T]he figure that has come to be most closely associated with process thinking in recent times is unquestionably Alfred North Whitehead, who articulated a comprehensive metaphysical system that conceived of the world as a unified, dynamic, and interconnected whole. Nowadays [Euro-Western] process philosophy has become almost synonymous with Whitehead’s work. Without in any way wishing to detract from Whitehead’s importance to the development of process thought, for the purposes of our present project we wish to distance ourselves from the association with Whiteheadian metaphysics. One reason for this is that Whitehead’s most systematic metaphysical treatise, Process and Reality (1929), is generally agreed to be opaque and at times so obscure as to verge on the unintelligible. ... [W]e have found that Whitehead is sometimes as much a liability to process thought—associating it with undesirable philosophical baggage and offputting prose—as he is a valuable exponent of it. In fact, we suspect that process philosophy has not received the attention it deserves partly because of its close association with Whitehead’s work.

From Section 4, Processes and Things

What is the difference between a thing, or a substance, and a process? ... Processes are extended in time: they have temporal parts. ... Equally central to the concept of process is the idea of change [or dynamicity]. A process depends on change for its occurrence. Traditionally, change has been construed as something that happens to things, or substances, typically conceived of as durable, integrated entities that are not dependent on external relations for their existence. Things, in this view, are the subjects of change, and processes merely track modifications in the properties of things over time, or describe means by which things interact with one another. This understanding leads to the assumption that processes always involve the doings of things. Processes therefore necessarily presuppose the prior existence of things. One problem with this view is that many processes do not in fact belong to particular subjects. Rain, wind, electricity, and light are all commonplace examples of subjectless or ‘unowned’ processes—processes that are not the actions of individual things. There are numerous subjectless processes in the living world as well: osmosis, fermentation, adaptive radiation, and so on. ...

Many processes are bona fide individuals—they are concrete, countable, and persistent units. Non-biological examples include whirlpools, flames, tornadoes, and laser beams. In biology, processes are, as we have already mentioned, dynamically stabilized at vastly different timescales: a matter of minutes for a messenger RNA molecule, a few months for a red blood cell, many decades for a human being, and up to several millennia for a giant sequoia tree. This stabilization can make it easy to mistake them for static things. But, more importantly, it allows them to play the role traditionally attributed to things that undergo processes in substance ontology. The only condition is that the relevant processes must be sufficiently stable on the timescale of the further processes that they in turn undergo. Enzymes can be treated as things because they are stable on the timescale of catalysis. Similarly, white blood cells are stable on the timescale of phagocytosis, alveoli are stable on the timescale of respiration, animals are stable on the timescale of reproduction, and so on.

We believe, then, that it is a mistake to suppose that processes require underlying things, or substances. This commonly held belief corresponds, unsurprisingly, to the original meaning of the term ‘substance’, which derives from the Latin word substantia—literally, that which stands under. In opposition to this view, we take nature to be constituted by processes all the way down. This represents a reversal of the substantialist position described above. Instead of thinking of processes as belonging to things, we should think of things as being derived from processes. This does not mean that things do not exist, even less that thing-concepts cannot be extremely useful or illuminating. What it does imply is that things cannot be regarded as the basic building blocks of reality. What we identify as things are no more than transient patterns of stability in the surrounding flux, temporary eddies in the continuous flow of process. ...

Processes come in many forms, shapes, and sizes. The spatio-temporal organization of a process and its spatio-temporal and causal relations to other processes determine its persistence and stability, and are also what grounds its properties and causal powers. As we have already noted, processes can be ‘pure’ dynamic activities, or they can be individuals exhibiting most of the characteristics typically attributed to things. Whereas things can generally be individuated by their spatio-temporal locations—things typically exclude other things from the regions of space-time they occupy—this is not typically the case for processes. Many processes have boundaries that are fuzzy or indeterminate, a feature with implications that we shall explore later. Processes are individuated not so much by where they are as by what they do. A series of activities constitute an individual process when they are causally interconnected or when they come together in a coordinated fashion to bring about a particular end. Many of the processes found in the living world, moreover, exhibit a degree of cohesion that demarcates them from their environment and thereby allows us to identify them as distinct, integrated systems—as entities in their own right.

From Section 5, Empirical Motivations

In this section we shall examine some well-established scientific facts about life that reveal the unsuitability of traditional substance metaphysics for representing biological reality and which have compelled us to adopt a processual stance towards the living world.

Although this book is primarily concerned with the life sciences, we do not think we should proceed without at least mentioning that the physical sciences already provide powerful motivations of their own for endorsing a process ontology. Nicholas Rescher has quipped that modern physics ‘puts money in the process philosopher’s bank account’, and it is easy to see why. The advent of quantum mechanics at the turn of the twentieth century led to the dematerialization of physical matter, as atoms could no longer be construed as Rutherfordian planetary systems of particle-like objects. This resulted in the demise of the classical corpuscular ontology of Newtonian physics, which had been one of the pillars of substance metaphysics since the scientific revolution. What had hitherto been conceived of as the ultimate bits of matter became reconceptualized as statistical patterns, or stability waves, in a sea of background activity.

- [The authors then offer examples explicating how metabolic turnover, life cycles, symbioses, and broader ecological interdependence pose major problems for a map-metaphysics of separation and stasis, and how process-relational frameworks solve those problems.]

- [In Section 6, Philosophical Payoffs, they offer thorough critiques of essentialism, reductionism, and mechanistic explanations, which they say should be "more appropriately understood as heuristic explanatory devices—as idealized spatio-temporal cross sections of living systems that conveniently abstract away the complexity and dynamicity of their biotic and abiotic surroundings and pick out only the causal relations that are taken to be most relevant for controlling and manipulating the phenomena under investigation." That is, they are like maps that should not be mistaken for the territory.]

- [Section 7, Biological Consequences, then "consider[s] some specific consequences for physiology, genetics, evolution, and medicine," which are fascinating and important but probably best read in their original level of detail. I'd like to do future posts on each.]

From Section 8, Conclusion

We are well aware that previous attempts to defend process ontology have often been met with considerable scepticism, if not downright hostility. One reason for this, in our view, is that process philosophers have frequently felt the need to introduce a new lexicon in order to come to terms with the processual nature of existence. ... However, as we hope this essay has demonstrated, it is not necessary to appeal to neologisms or resort to opaque prose to make the case for process. Thing-locutions, despite their pervasiveness, do not have to be taken at face value. After all, our linguistic conventions are not always aligned with our ontological convictions; which is why, for instance, we continue to speak of ‘sunsets’ and ‘sunrises’ even centuries after the Copernican revolution. It suffices that we realize that English grammar, like that of other Indo-European languages, exhibits a clear bias towards substances, which may well be rooted, at least in part, in our cognitive dispositions.*

Beyond any such inherent bias, we surmise that the widespread prevalence of substance ontology also reflects the fact that in many circumstances it does the job sufficiently well. The relation between substance and process ontology is not completely unlike the relation between classical and modern physics. Just as classical physics provides a convenient approximation of middle-sized physical entities moving at relatively slow speeds but does not constitute an accurate description of physical reality, so substance ontology provides a serviceable characterization of biological entities, especially when considered over short temporal intervals, despite being a fundamentally inappropriate description of the living world. But, although it might seem more intuitive to regard organisms as things than as processes, the situation quickly begins to reverse when we start giving due consideration to time. ...

The more we learn about life, the more necessary a process perspective becomes. This is particularly the case with regard to the increasing realization of the omnipresence of symbiosis, which directly challenges deeply entrenched substantialist assumptions about the living world. Thus the empirical findings of biology are inexorably driving us towards processualism, even if it is less intuitive* than substantialism. It is interesting to observe that physics, which has traditionally been regarded as the more advanced science, was pushed towards process ontology about a century ago (as was argued by Whitehead and others), and now biology—if we and the other contributors to this volume are correct—is following suit. Might this perhaps be an indication that the shift from substantialism to processualism is just something that all sciences go through as they develop?

*It's massively important that many non-Indo-European languages are not nearly as noun-centric as ours! See, e.g., https://www.native-languages.org/definitions/verb-based.htm. What we consider more intuitive may not be a universal matter of human nature.