Less Wrong = More Right (Brain Hemisphere?)

Directions of seeing reality correspond to halves of our brains. Maps to the left, terrain to the right.

About a year ago, I encountered a bunch of research that absolutely blew my mind, while at the very same time it bolstered what I already thought. Not gonna lie, that's a pretty satisfying combo. Prepare to have your mind blown too.

I was a few years into the research for the book/wiki project underlying this blog. I'd spent many, many hours outside of my day job on the supremely nerdy task of getting the basic gist of dozens of academic arenas: physics, ecology, health, social sciences, and more. From reading books and their critiques, swimming around in virtual meshworks of Google Scholar searches and cross-links, connecting with experts, and other generalist methods, I already had my ideas in something pretty close to the shape you see on this blog. If you've read any other posts here, you know the recipe. First ingredient: two broad directions of the practical metaphysical frameworks that structure all of our thoughts, one statically separating things out, essentializing and mapping them, and the other dynamically integrating them as relational processes co-constituting a complex terrain. Second ingredient: all the converging evidence showing the latter to be how things really are. Third ingredient, awareness of that comparison being a leverage point for personal and social transformation. All well and good.

Then my research turned to what this basic comparative metaphysics had to say about the gist of cognitive neuroscience, and what the gist of cognitive neuroscience had to say about this basic comparative metaphysics. And just ...holy shit, y'all. These two recurring directions seem to correspond awfully closely to the two hemispheres of our brains. Maps to the left, terrain to the right. The world we perceive and build depends heavily on which side we give the last word. We may not be able to understand ourselves, let alone the reality of which we are a part, without understanding this innate duality.

The most prominent compiler of evidence for this theory about the brain's hemispheres is Iain McGilchrist. He's a renowned British psychiatrist, neuroscientist, literary scholar, and philosopher, best known for writing the 2009 book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (hereafter TMAHE). (I read a 2019 expanded edition.) He summarized highlights of TMAHE in a short and accessible e-book in 2012, The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning: Why Are We So Unhappy?. I confess I have not read McGilchrist's most recent (2021) and ambitious (1500 page!) book, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World, but I've read quite a few in-depth reviews of it, along with author interviews and some of McGilchrist's own fairly prolific writings—enough to confirm that the newer book's basic model of the two hemispheres largely recapitulates the one that McGilchrist presented a decade and a half ago in TMAHE. Most of that newer tome is dedicated to exploring more specific epistemological and ontological nuances within process-relational philosophy than this blog aims to tackle.

The Gist of Modern Knowledge on Brain Hemispheres

McGilchrist distances himself emphatically from shallow pop-psychology models of a verbal and logical left-brain versus a creative and emotional right-brain. Language, logic, creativity, emotions, and other functions involve both sides. Instead, he builds a convincing case that the two hemispheres asymmetrically handle not different topics, but rather, different ways of attending to the world—not the what but the how. Much evidence is drawn from unfortunate cases of damage to one hemisphere or the other, as well as from split-brain surgeries (corpus callosotomies) done to address epileptic seizures; luckily, modern experiments and imaging manage to distinguish the hemispheres' operations in healthy subjects, such as by anaesthetizing one side of the brain or the other. The evidence is not limited to humans. This lateralization goes back hundreds of millions of years and is evident in species from mammals, to birds and reptiles, to nematode worms.

The core observation is that animals need to attend to the world in two distinct, complementary ways. The first way is broadly vigilant, integrative attention. It entails being present and open to the unknown, monitoring for risks (predators, rivals, pains) and opportunities (food, shelter, mates). That’s the predominant mode in the right hemisphere (RH), which is linked more strongly to the left side of the body. The second way is narrowly focused. It involves separating a particular risk or opportunity from its context (like a seed from surrounding gravel), abstractly re-presenting and classifying it based on prior knowledge (is the seed edible or not), and acting on it or manipulating it. That’s the primary domain of the left hemisphere (LH), which, you guessed it, is linked more strongly to the right side of the body.

It's not really feasible for these different types of attention to engage the exact same places in the brain at the exact same time, sort of like a single-lens camera can't have both a deep and a shallow depth of focus at once. Because our ways of attending to the world happen concurrently, they have evolved spatial separation, perhaps moreso as complexity increases up to human brains' hundred trillion connections. The separation isn't absolute. However, even small asymmetries matter. In humans and other placental mammals, the left and right hemispheres are separated by the corpus callosum operating as a sort of traffic light, both inhibiting and facilitating crossings. McGilchrist says that the broadly receptive RH is the primary mediator of experience, which it presents to the task- and control-oriented LH to unpack; when the brain is operating in its proper balance, the RH then reintegrates the LH's work into the big picture, giving it meaning.

Each type of attention brings along a whole entourage of associated traits. This is where the brain hemispheres' modes really start to look like two directions of metaphysics, or beliefs about the nature of things that fundamentally constitute reality. The LH preferentially deals with abstracted generalizations and ideals while the RH engages more with concrete specificities. The LH, interchangeability and conformity; the RH, peculiarity and uniqueness. The LH, precision and quantities; the RH, indeterminacy and qualities. The LH, flatness and linearity; the RH, dimensions and curves. The LH, segmentation and reduction to parts; the RH, emergence of a gestalt. The LH, internal coherence and predictability; the RH, correspondence with observations and sensory experience, however novel or seemingly contradictory. The LH, constancy and separateness; the RH, processes and relationality. One review of The Matter With Things summarizes:

The research shows that the left hemisphere is less aware of its surroundings and tends to ignore what is [deemed] irrelevant to its purpose: it sees clearly, but it sees little. Inclined to “either/or” thinking, it enables us to manipulate the world. ... It is optimistic, purposive, precise, certain and confident—even when it gets things wrong. The right hemisphere, by contrast, is better at understanding the world in all its complexity. It is inclined to “both/and” thinking and more willing to change its view in the light of new evidence. It is reflective, empathic, exploratory, more uncertain and self-deprecatory than the left hemisphere.

Another recaps:

The RH focuses on what is new and is alive to the possible; the LH focuses on the familiar and certain. The RH's ability to entertain uncertainty equips it to deal with things the LH does not understand: ambiguity, metaphor, irony, humor. The LH world tends to fixity and stasis, the RH towards dynamism and flow. The LH sees things as explicit and decontextualized—hence literally; the RH has an eye for the implicit and the context. The LH is the hemisphere of the inanimate (including tools-though fascinatingly not musical instruments), while the RH prefers the animate. ... Countless studies demonstrate that in many matters the LH is obtuse, overconfident, inclined to confabulation, angry, and often wrong.

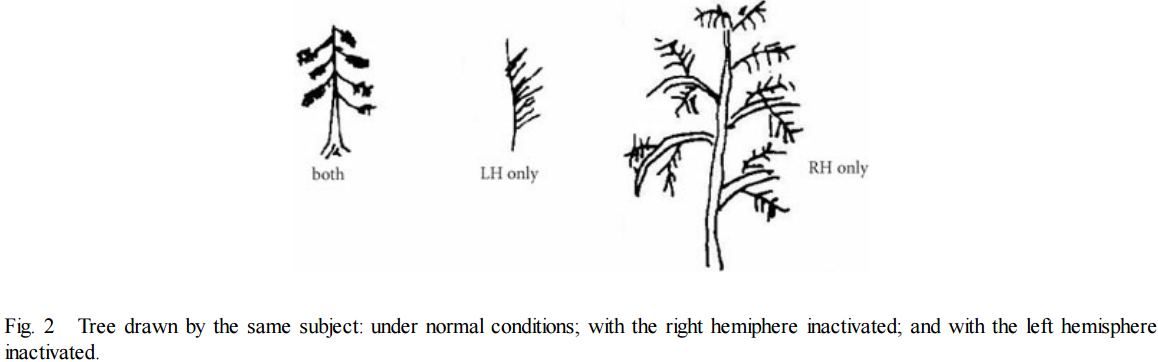

Examples abound illustrating these trait clusters. For instance, people with damage to their right hemispheres commonly exhibit pathological denial, intransigence, and irrational optimism. They'll stick to their existing point of view regardless of counter-evidence—even refusing to acknowledge deficits as severe as left-side paralysis after right-hemisphere stroke and making up bizarre excuses for not being able to move (anosognosia for hemiplegia). Delusions also tend to implicate right-hemisphere dysfunction. Another striking example illustrates how each hemisphere draws a tree, in a single person with the activity of one or the other temporarily suppressed. The LH version is not only an abstracted icon of a tree, it also totally ignores everything but the right side, i.e., what's graspable with the right hand which is controlled by the LH (hemispatial neglect).

Perhaps even more fascinating than the hemispheres' distinct traits is their operating relationship with, or against, each other. Crucially, much like the terrain can contain its map but not vice versa, the RH can encompass and integrate the perspective of the LH but the LH is incapable of embracing the perspective of the RH. As summarized by science correspondent Shankar Vedantam in 2019 on NPR's Hidden Brain show:

With its big-picture view of the world, the right hemisphere can see what the left hemisphere is doing, see the value that it produces. But the left hemisphere, with its narrow view of reality, doesn't recognize the value of the right. In other words, the left hemisphere not only sees a narrow view of the world, it believes that the narrow view that it sees is all there is to see.

Or as McGilchrist writes in TMAHE:

The world of the left hemisphere, dependent on denotative language and abstraction, yields clarity and power to manipulate things that are known, fixed, static, isolated, decontextualized, explicit, disembodied, general in nature, but ultimately lifeless. The right hemisphere, by contrast, yields a world of individual, changing, evolving, interconnected, implicit, incarnate, living beings within the context of the lived world, but in the nature of things never fully graspable, always imperfectly known—and to this world it exists in a relationship of care. The knowledge that is mediated by the left hemisphere is knowledge within a closed system. It has the advantage of perfection, but such perfection is bought ultimately at the price of emptiness, of self-reference. ... Where the thing itself is 'present' to the right hemisphere, it is only 're-presented' by the left hemisphere, now become an idea of a thing. Where the right hemisphere is conscious of the Other, whatever it may be, the left hemisphere's consciousness is of itself.

It matters that our left hemispheres have a tendency to be up their own asses, so to speak, because they are capable of suppressing our right hemispheres. As (my favorite!) philosopher Mary Midgley wrote in a book review, "the specialist partner does not always know when it ought to hand its project back to headquarters for further processing. Being something of a success-junkie, it often prefers to hang on to it itself. And since we do have some control over this shift between detailed and general thinking, that tendency can be helped or hindered by the ethic that prevails in the culture around it." In turn, the extent to which we let the left hemisphere quash the right shapes the relationships, systems, and cultures that we co-create.

Currently, despite the abundant and growing evidence for the RH's privileged access to the fullness of reality's terrain, as Vedantam says, "we live in a world that prizes what the left hemisphere offers and has contempt for what the right hemisphere brings to the table."

The Need for Euro-Western Culture to Re-engage the RH

The second, more controversial half of TMAHE elaborates on this point that modern Euro-Western culture elevates and operationalizes left-hemisphere analytical conclusions while demeaning the right-hemisphere's process-relational ways of attending to the world. In the account of McGilchrist (which is echoed by many others), the map-metaphysics discounting of RH contributions can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, exemplified by thinkers like Parmenides and Plato. René Descartes consolidated it further in the 1600s. The LH view mistaking the map for the terrain has since become more societally entrenched via developments like the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions and the go-to conceptual maps and metaphors they've given us.

In the last chapter, McGilchrist walks through "what the world would look like if the left hemisphere became so dominant that, at the phenomenological level, it managed more or less to suppress the right hemisphere's world altogether." The "bits" of anything would come to seem more important as the whole would be seen as no more than the sum of mechanistic or algorithmic parts. Increasing specialization and technicalization would prioritize quantitative information over qualitative knowledge and grounded experience, and far over wisdom, seen as ungraspable and less real. The world would become more virtualized, bureaucratized, surveilled, and alienated. Theory would be reified. Essentialized categories (sex, race, nation, religion, etc.) would be set in competition. Anger would not be counterbalanced by empathy and there would be a rise in intolerance. Control and exploitation would be the default relationship among humans and between humans and the rest of nature. And so on.

That all sounds uncomfortably like the world we live in. However, McGilchrist emphasizes rather different cultural flaws arising from left-hemisphere thinking than I or many others would, in ways that I think display major and ironically left-brained limitations. For a start, TMAHE's second half is titled "How The Brain Has Shaped Our World," but it deals only with Euro-Western culture. "Partly this is a function of my ignorance," McGilchrist explains; "partly the scope of such a [globally inclusive] book would threaten to be unmanageable." He does grant that other cultures seem to enjoy better hemisphere balance. Still, even within this Euro-Western-centric narrowing of attention, there's a glaring absence of colonialism, racial hierarchy, patriarchy, or extractive capitalism as clear and impactful examples where left-hemisphere thinking provides a load-bearing foundation. The material impact of rich white men's self-aggrandizing claims to the highest LH-style "rationality" and the importance of misogyny, racism, and classism in keeping the RH down are muted. In TMAHE, McGilchrist sometimes seems more offended by analytic philosophy and abstract modern art than by harms like rigid gender binaries, the oppression of Black and Indigenous peoples, or the reduction of our lives and our planet into numbers on corporate spreadsheets. (I'll grant that McGilchrist is a proponent, especially more recently, of social and ecological balance and bottom-up solutions to climate and environmental degradation.)

These ironic limitations extend beyond the four corners of the book. McGilchrist's disdain for postmodernism and bureaucracy, and his argument in the second volume of The Matter With Things for God (of a sort), make him appealing to some truly awful Christian conservatives desperate for intellectual cover. If you search him on Google, you'll find him engaging with right-wing dipshits like Jordan Peterson, Rod Dreher, and Hillsdale College—yes, the whole college is a dipshit. It's a matter of definition and observation, not opinion, that process-relationality is incompatible with their individualistic, monocultural, patriarchal, extractive, theocratic/hyper-capitalistic/techlord-aligned right-wing politics. Even the slightest inquiry into such politics with a brain-hemispheric or comparative-metaphysics lens shows LH map-metaphysics to be obviously load-bearing. But McGilchrist's books don't explicitly do that inquiry. In the absence of a direct smackdown, his right-wing fans seem to focus on the latter parts of his books as if they scientifically justify, not an attitude of pervasive sacredness, but their particular religious beliefs.

All this, along with a downright insulting treatment of neurodivergence and some other content and context clues (perhaps even the Nietzchean "master" language of the titular metaphor of TMAHE), suggests that McGilchrist's own uplifting of broadly integrative thinking could be pushed further than he takes it. In other words, most of the critiques I have of McGilchrist's work could be addressed by more consistently applying the process-relational lessons of TMAHE's own first half: zooming out more broadly and engaging more openly with sources of deeper cultural expertise in holistic thinking. I think it could be particularly generative to put McGilchrist's work into conversation with Citizen Potawatomi Nation member Robin Wall Kimmerer's concept of "two-eyed seeing," or Apalech Clan member Tyson Yunkaporta's excellent Right Story, Wrong Story. I suppose McGilchrist's bridging to right-wing conservative men does present some possible foot-in-the-door opportunities for teaching them the validity of reality-based, right-hemisphere values such as inclusive pluralism, positive-sum reciprocity, and environmental stewardship... if they ever learn to read open-mindedly for integrative comprehension rather than ignoring everything they deem irrelevant to supporting their favored hierarchies. Bit of a Catch-22 there, since that's mostly RH stuff, but maybe someday.

I wonder: Could McGilchrist's first-mover dominance of this intersection of cognitive science with culture-wide metaphysical frameworks, combined with the conservative and religious tilt of his books and their audiences, contribute to progressives so far largely missing the opportunity to leverage the cognitive science of brain hemispheres in favor of our reality? Especially in the context of all the other convergent science establishing not just the possibility but the existing reality of an interdependent, non-zero-sum, process-relational world, it strikes me this growing branch of cognitive science might just help get more folks aligned toward a shared direction of regenerative coexistence. People are already cultivating a less fractured and hierarchical world in the cracks of our LH-dominated one; couldn't restoration of a healthy respect for process-relational RH thinking—under whatever labels—be an especially powerful one of those not-the-master's-tools to advance that project?

Ultimately, the epistemic status* of McGilchrist's model of the hemispheres' respective modes is that of a research-supported hypothesis. It's not an idea that has been adopted as central to cognitive science theories by that broader scientific community, though as far as I can tell that part hasn't been heavily criticized either. McGilchrist himself writes at the end of TMAHE with admirable intellectual humility that "if it could eventually be shown definitively that the two major ways, not just of thinking, but of being in the world, are not related to the two cerebral hemispheres, I would be surprised, but not unhappy. Ultimately what I have tried to point to is that the apparently separate 'functions' in each hemisphere fit together intelligently to form in each case a single coherent entity; that there are ... consistent ways of being that persist across the history of the Western world, that are fundamentally opposed, though complementary, in what they reveal to us; and that the hemispheres of the brain can be seen as, at the very least, a metaphor for these."

This blog post, of course, has even lower epistemic status: it's very condensed and stripped of nuance that it took McGilchrist hundreds of pages to explain, citing thousands of underlying case studies and peer-reviewed articles. Accordingly, it would be quite reckless of me to suggest that fascists are just worse at using their whole brains than the rest of us, even without literal brain worms, because they demean and suppress their right brain hemispheres' contributions. It would be even more unseemly to stretch that into a jokey insult that they're half-lobotomized by their ideological commitments.

But fuck those half-wit simpletons. The world would be better off with a snappy popular heuristic that thinking like a fascist is basically only using half your brain—the dumber half. That's far less wrong than going without that concept and overly tolerating fascists' map-metaphysics mistakes about things.

*This is a note that was sometimes made at the "rationalist" blog Slate Star Codex, and it's a nice practice. Some other aspects of that style of "rationalism" are obviously more aligned with left-brained map-metaphysics than process-relational frameworks, a topic I'll surely rant about at some point on here.